5 Common Myths about Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)

5 Common Myths about Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) refers to various methods that supplement or support oral speech for individuals with speech impairments. AAC systems and devices enable users to communicate wants, needs, ideas, and opinions when faced with challenges verbalizing.

While AAC is an invaluable communication option for many, misconceptions still exist surrounding its use and effectiveness. Certain myths about AAC can lead to avoidance of AAC or improper implementation. Dispelling these myths is key to promoting broader acceptance and optimal use.

We will tackle 5 prevalent myths about AAC and present the facts to overcome misinformation. Understanding the reality behind common AAC myths empowers individuals to make informed decisions about AAC and properly utilize it to improve communication and quality of life.

1. AAC is a machine that can produce speech

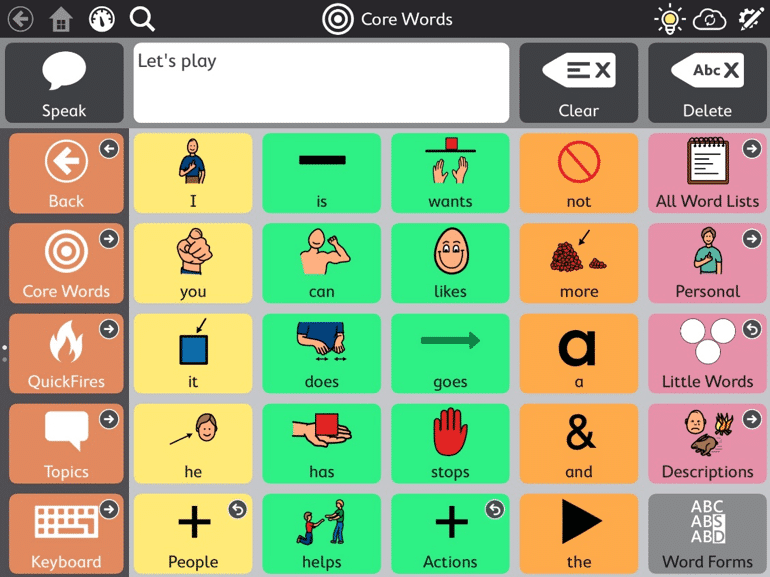

Not true. It is much more than that! The two main types of AAC are unaided communication and aided communication. Unaided communication does not require additional equipment. This includes pointing, facial expressions and even sign language. Aided communication requires tools to support communication. Tools may be low-tech AAC such as symbols, pictures, communication charts and core word boards and tools can be high-tech AAC such as speech-generating devices.

2. Only children who don’t use words need AAC

Not true. AAC can be viewed as a transitional tool for children with language delays. Young children who use AAC transition into spoken language once they are ready. It can be viewed as an ‘add-on’ or support, especially when they are still learning to understand language.

3. AAC will keep my child from using words

Not true. In fact, it is just the opposite! Research actually shows that using AAC helps children make gains in their expressive speech because through AAC they learn the benefits of communicating and it can reduce their frustration.

4. A young child is not ready for AAC

Not true. For children with physical disabilities, motor disorders or learning difficulties, it is best to introduce AAC as young as possible. This often starts with unaided communication such as pointing and then gradually moves onto speech-generating devices depending on their abilities.

5. High-tech AAC is better than low-tech AAC

Not true. One type of AAC is not better than another. There are pros and cons with each method and it depends on a child’s abilities and what they prefer. For children with communication difficulties, a ‘Total Communication’ approach is usually encouraged as it makes use of the different modes of communication skills a child already has. For example, a child can say “hi” to a friend by waving a hand, point to a name card when the teacher is taking attendance, and ask for a snack using a core word board.

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)

is a term that encompasses communication methods used to supplement or support speech for individuals with impairments in the production or comprehension of spoken or written language. AAC is utilized by individuals with a wide range of speech and language impairments, including cerebral palsy, intellectual impairment and autism. AAC can be a permanent addition to a person’s communication or a temporary aid with the options of low tech and high tech. Our goal is to enable an accurate understanding of what AAC is, who it can help, and how to approach it effectively.

Reference: https://www.cdchk.org/parent-tips/five-common-myths-about-aac/